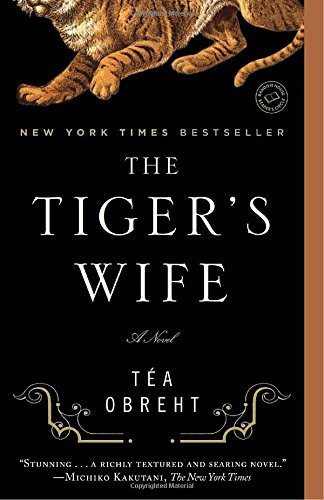

NATIONAL BOOK AWARD FINALIST • NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY The Wall Street Journal • O: The Oprah Magazine • The Economist • Vogue • Slate • Chicago Tribune • The Seattle Times • Dayton Daily News • Publishers Weekly • Alan Cheuse, NPR’s All Things Considered

SELECTED ONE OF THE TOP 10 BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times • Entertainment Weekly • The Christian Science Monitor • The Kansas City Star • Library Journal

In a Balkan country mending from war, Natalia, a young doctor, is compelled to unravel the mysterious circumstances surrounding her beloved grandfather’s recent death. Searching for clues, she turns to his worn copy of The Jungle Book and the stories he told her of his encounters over the years with “the deathless man.” But most extraordinary of all is the story her grandfather never told her—the legend of the tiger’s wife.

Look for special features inside. Join the Circle for author chats and more.

Author One-on-One: Jennifer Egan and Téa Obreht

Jennifer Egan is the recipient of the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for her novel A Visit from the Goon Squad, which was also awarded the National Book Critics Circle Award. She is the author of The Keep, Look at Me, and the story collection Emerald City. Her stories have been published in The New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, GQ, Zoetrope: All-Story, and Ploughshares, and her nonfiction appears frequently in The New York Times Magazine. She lives with her husband and sons in Brooklyn.

Jennifer Egan: One of the central powerful relationships in the book is between Natalia and her grandfather: it’s not the type of relationship we usually see as the primary relationship in a novel. Could you talk a little about that grandparent-grandchild relationship, your feelings about it in your own life and how it became central in this novel?

Téa Obreht: I grew up with my grandparents on my mother’s side, and they essentially raised me. As a kid, you resist the idea of your own parents having had lives and pasts of their own. Snuff me out if I’m wrong here, but I see that as something prevalent in your novel A Visit From the Goon Squad: a sense of the parent-child relationship being very tense and of children not wanting to live in their parents’ shadow. When you’re growing up, the lives of your parents aren’t that fascinating, but there is this fascination with grandparents. Because of that great amount of time that has passed between their youth and yours, and the fact that they lived entire lives before you even got there, you can’t really deny their identity as individuals prior to your existence they way perhaps you can with your parents. There’s also an awareness that the world was very different when they were living their lives.

Egan: Animals play such an enormous role in the novel: the tiger, the dog, Sonia the elephant, Darisa who seems to be part-human, part-bear. You write so movingly about animals that I found myself close to tears every time you wrote about the tiger from the tiger’s point of view. Do you have a strong connection to animals in your life? How is it that animals end up figuring so enormously in this story?

Obreht: I’m definitely, it turns out, the kind of person who’s a total National Geographic nerd. I’m there for all the TV specials. As I’ve gotten older I think my awareness of the natural world and animals’ relationship to people–both culturally and biologically–has grown. It was fun to write from the point of view of the tiger, and emotionally rewarding, but I think the animals also serve almost as markers around which the characters have to navigate. I don’t think that was something I did consciously, it just sort of happened. There is something jarring about seeing an animal out of place: there’s a universal feeling of awe when you see an animal, particularly an impressive animal, out of place.

Egan: There are really two worlds in the book which mingle and sometimes intersect: there’s the present day political, medical, scientific situation in which Natalia operates, and then there’s this more mystical, folkloric world of the grandfather’s past. How did these define themselves in your mind? Was it hard to move between them?

Obreht: Pretty early on in the writing I realized that mythmaking and storytelling are a way in which people deal with reality. They’re a coping mechanism. In Balkan culture, there’s almost a knowledge that reality will eventually become myth. In ten or twenty years you will be able to recount what happened today with more and more embellishments until you’ve completely altered that reality and funneled it into the world of myth.

A Letter from the Author

A Letter from the Author

Téa Obreht was born in Belgrade in the former Yugoslavia in 1985 and has lived in the United States since the age of twelve. Her writing has been published in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Harper’s, and The Guardian, and has been anthologized in The Best American Short Stories and The Best American Nonrequired Reading. She has been named by The New Yorker as one of the twenty best American fiction writers under forty and included in the National Book Foundation’s list of 5 Under 35. Téa Obreht lives in New York.

After completing my first novel, The Tiger’s Wife, I’ve found myself indulging in a sentimental mood. I pretend that this is due to my need to retrace my steps, to see how it all came together, and, by remembering what I did before, somehow speed my next project along; in fact, I am probably just procrastinating or being insufferable, mulling over memories that, due to the late hours, were doomed to an impregnable haze a long time ago. I dig through my “notes”: folded scraps of paper, the backs of torn-open envelopes where I doodled plot points and lines of dialogue, index cards with cryptic inscriptions—“BUT WHAT HAPPENED TO THE WATERMELON?!?!?”—punctuated as though I’d had some kind of civilization-saving breakthrough.

For whatever reason, as I go through my notes, I spend much of my time revisiting the evolution of my characters. Who’s been there the longest? Who was thrown out at the last minute? Who was the life and soul of the first draft, and then ended up with one dialogue in the third? Who’s been renamed, transformed completely into somebody else?

>In some ways, the answers to these questions are both pointless and intensely personal, like telling a long-distance friend about how you’ve fallen in love with a person they have never met: they can listen politely while you rattle off a list of traits or events, but a whole world of experience separates the storyteller from the listener. But I do believe that thinking about these things gets back to the vital question of artistic control, and the surprising ways in which your work takes on a life of its own. In The Tiger’s Wife, I found, of course, that core of the cast members— a tiger, his “wife,” a little boy—were all together at the outset, in the spring of 2007, peopling a lackluster short story about a deaf-mute girl who arrives in a snowbound village in pursuit of the escaped tiger with whom she performed in a traveling circus. But, to my surprise, I also found a then-minor character called Dariša the Bear.

Originally, he was a mean drunk, a ruthless and uncomplicated villain, hardened by religious fanaticism, and I wanted the reader’s revulsion with him to be simple and complete. When the story began to expand, and the village of Galina and the characters who live there expanded with it, there was no room for Dariša; his kind of villainy had been eclipsed by a far more sinister character, and he was extracted and put away. He wouldn’t find his way into the book again until one afternoon, almost a year later, when I found myself at the Moscow flea market of Ismailova—a townie-shunned tourist trap against which the few Russians I knew had cautioned me—and among the predictable lacquered matrioshkas, bootleg DVDs, prints of Soviet propaganda and fake Fabergé baubles, I met the bear-man. I can’t picture his face anymore, but I do remember that he had pitched his booth at the top of a wide, stone staircase, and that, draping down from the top like water, were the pelts of maybe two dozen brown bears of all shapes and shades, mouths agape. We must have talked—I can’t imagine not asking him where he was from, or whether he had done the killing himself—but I don’t remember the conversation. What I do remember is going home that afternoon and dredging up a man reincarnated as Dariša the Bear, a hunter and taxidermist whose obsession with death, drawn from great personal loss, is rooted in his desire to understand and preserve the majesty of things once living.

I would never have thought, at the outset of all of this, that of all the characters in The Tiger’s Wife, I would end up feeling closest to Dariša. Perhaps it is because in a roundabout way I have ultimately spent so much time with him; perhaps it is because, in the end, he becomes a man who seeks to capture life in the absence of it. After all, isn’t that what storytellers really do?

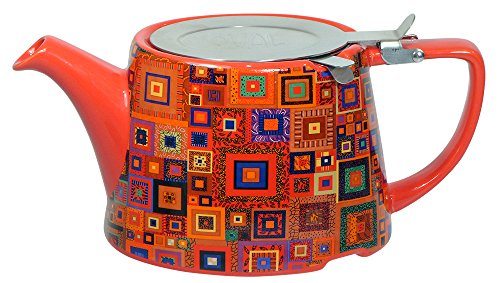

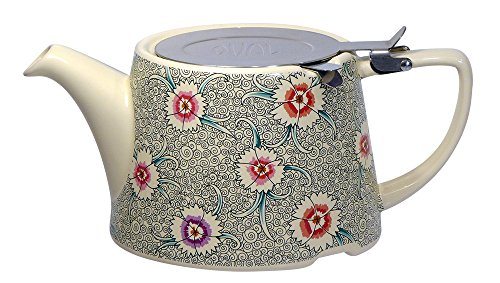

Product Features

A Letter from the Author

A Letter from the Author

A memorable mixture of myth and the ugly reality of a region torn by war A delight to read. This was a delight to read. Obreht weaves together myth and hard-core realism in telling the story of a young doctor delivering care in a war-rent region of the Balkans where she had once lived. Part of her former homeland has become hostile to those of her ethnic origins, which affects her ability to travel safely and interact comfortably with her former neighbors. Her grandfather, also a doctor, is a powerful presence in the novel, and adds two powerful mythic threads to the story. This was…

Good Read Maybe this is a five star book and I am a three star reader. There were so many outstanding reviews that I wonder what is wrong with me? On re-read, I did give the book a third star. In some passages I liked the fantasy, but bad punctuation killed the liking. I had to do mental math to determine if some passages were here and now or in the yesteryear. I am not fond of math. The author did connect the characters’ fantasy with their reality.Thank you, Ms. Obreht, for a good read.

The Tiger’s Wife A Novel A difficult but worthwhile book to get through. The author is a wordsmith. Bringing in new characters,.and jumping into their stories was confusing at times; but pulling it all together was masterful. Explaining every detail you could actually see the space where the action was taking place. Again a difficult not an easygoing read but a great read. One that takes time and thought.